The Spun Bearing: A Century of Automotive DOHC Engines

“Power output is finally dependent upon weight of air efficiently burnt per minute, and this in the end is fixed absolutely by the breathing power of the valve gear.” – Laurence Pomeroy, in The Grand Prix Car

That is the opening quote of Griffith Borgeson’s, The Classic Twin Cam Engine. I hesitate to tread the same ground, but this is a bit of a milestone and I haven’t seen it recognized in print yet (though I am quite possibly ignorant of other efforts reporting on this anniversary).

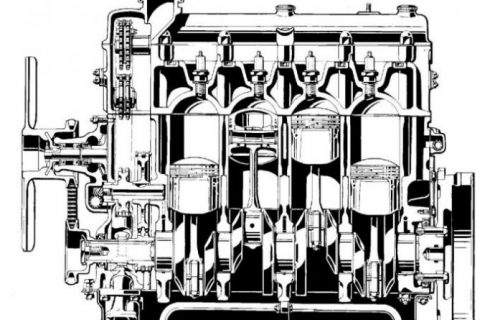

Twin cam engines have been installed in automobiles beginning in the year 1912. The twin cam engine made its automotive debut in a Peugeot grand prix car. The engine, called the L76, was a four cylinder, four valve per cylinder, undersquare design (undersquare meaning the stroke is greater than the bore – in the case of the GP Peugeot its bore was 110 mm and stroke was 200 mm). These were great lumbering beasts – this was a 7.6L four cylinder after all – and it produced a mere 130 HP.

It utilized hemi-spherical combustion chambers. Given the slow burn times of the low quality fuel available then, the hemi head made sense. The time it took to successfully burn an amount of fuel, that would produce a suitable power output, restricted engine RPM. (But that wasn’t the reason for the huge stroke on the L76, that was due to the fact that the bore and stroke selected for the L76 just happened to be the maximum the regulations for the race allowed.)

Since 1912 a lot has changed, fuels certainly have, metallurgy has, and engine electronics – which at the time involved magnetos and manual spark advance – have automated the most minute portions of the combustion process, allowing for an almost infinite mapping of engine loads and RPM. But the reason for using twin cams has not changed.

Prior to utilizing an overhead cam design, T-head and L-head engines predominated. Overhead valve engines (with a low mounted camshaft and valves above the combustion chambers) came along in the same time frame. But the twin cam design had the advantage (over the pushrod OHV engine) of near direct valve actuation (which the T-head and L-head engines did also). But, the combustion chamber was significantly more efficient in the twin cam design than either the L-head or T-head designs.

The twin cam design allows for better breathing, all else being equal. Given a sufficiently inclined valve orientation in the cylinder head, the total opening of the valvetrain could actually be bigger than the area described by the bore of the cylinder. That allows for more air to be ingested. And the more air you can move through an engine the more efficient it becomes.

To quote Borgeson, “With a wide included angle one could use somewhat larger valves and ports, achieve more straight-through gas flow and thus better breathing and burning. With the centerline of the cylinder head clear, the spark plug could be located in the combustion chamber’s geometrical centre, insuring uniform flame travel throughout the mixture and the most rapid propagation of the flame-front throughout its mass.”

In the first fifty years, twin cam engines were mostly restricted to extremely expensive passenger cars and racing cars. It has been the last quarter of a century that has seen a proliferation of twin cam designs move from the expensive makes down into the mass market marques.

Before World War II, BMW had experimented with a twin cam engine. The prototype twin cam engine BMW built was the M318 that was designed and built in the late 1930s. It utilized a 72 mm bore and 82 mm stroke giving it a displacement of 2 liters. Output was 120 BHP at 6,250 RPM. Further development promised 145 BHP at 7,000 RPM, but the war ended its development prematurely.

After the war it took 16 years before a twin cam engine was offered in a BMW, and then it was restricted to racing. It was the M107S two cylinder 700cc boxer motor with a trick valvetrain installed in racing versions of the BMW 700 (a very significant car for BMW that doesn’t get enough credit).

In the late 1960s BMW experimented with a twin cam four cylinder (proposed for the 2002). Two different twin cam cylinder heads (with different valve actuation) were tested but didn’t provide the HP increases hoped for and were subsequently dropped.

In 1983 BMW produced the A30 four cylinder with a twin cam head, but of course that was a motorrad engine. Then, with the advent of the M50 in 1989, twin cam technology returned to a BMW inline six cylinder. Since then twin cam designs have been common for BMW automotive engines.

Now of course the twin cam cylinder head is crammed chock full of Valvetronic, spark plugs, and direct fuel injectors. But the fundamentals remain the same as in 1912, maximize the breathing power of the engine. What has happened in the interim has been the advances in fuel and engine management that have improved both power and efficiency.

The designers of the 1912 Peugeot L76, known as ‘the Charlatans’, would be proud to see the fruit of their labors a hundred years later. I’ll raise a glass to Henri, Boillot, Goux, and Zuccarelli, Les Charlatans.

Author: Hugo Becker

Source: http://www.bmwblog.com/2012/02/19/the-s ... c-engines/